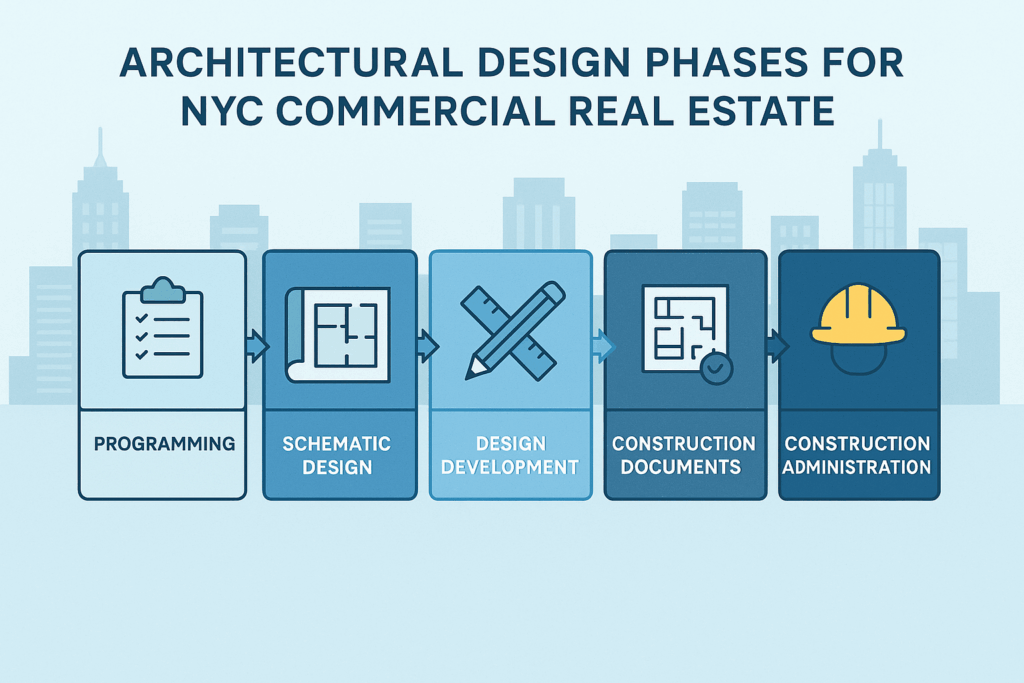

Commercial real estate development in New York City is a complex undertaking requiring careful planning and coordination. One effective way to navigate this complexity is by following a structured architectural design process from start to finish. According to the American Institute of Architects (AIA), an architectural project typically progresses through five primary phases. In practice, we include a preliminary Pre-Design phase as well, making it six key stages in total. Understanding these architectural design phases (or project stages) helps developers and property owners anticipate what’s next, keep projects on track, and manage expectations. A phased process also ensures that critical decisions are made in the proper sequence – from initial concept and feasibility all the way to construction and occupancy – which is especially important in NYC’s high-stakes development environment.

In this guide, we explain each of the six major phases – Pre-Design, Schematic Design, Design Development, Construction Documents, Bidding & Negotiation, and Construction Administration – specifically tailored to commercial projects in NYC. For each phase, we outline what it includes (deliverables, typical timeline, stakeholder involvement) and what clients should expect in terms of coordination, approvals, and costs. By breaking the project into these manageable stages, everyone involved can stay aligned and ensure a successful outcome.

Pre-Design Phase (Programming & Feasibility)

Before any design drawings begin, the Pre-Design phase (also known as Programming or Feasibility Study) lays the groundwork for a successful project. This initial phase is all about information-gathering and defining the project’s goals, requirements, and constraints. The owner/developer and architect work together to establish the framework for the development – determining what will be built, where, and why. For a commercial project in NYC, Pre-Design often involves studying the site’s conditions and the project’s viability before committing to a design direction.

During Pre-Design, the team will typically conduct feasibility analyses such as site studies and zoning investigations. In a city like New York, a thorough zoning analysis is critical at this stage to confirm what can be built on the site (allowable floor area, height, usage, etc.) under NYC’s complex zoning codes. The architect will also help the owner clarify the project program – essentially, the list of spaces and functions the building needs to accommodate (e.g. square footage of offices, retail areas, lobbies, etc.).

Additionally, preliminary budget targets and timeline expectations are discussed so that everyone understands the financial and scheduling parameters from the outset. This phase may involve other due diligence tasks as well, like commissioning a land survey, reviewing any existing structures or environmental conditions on the site, and sometimes a pro forma or market analysis on the development’s economic feasibility. In short, Pre-Design is about uncovering all the key facts and constraints early on. Investing time in this planning stage will set the path for the entire project and help avoid costly surprises down the road.

Pre-Design – What to Expect:

Deliverables:

Typically, a feasibility report or program document is produced, summarizing the project’s requirements and viability. This might include a site analysis report (documenting site conditions, zoning allowances, and any restrictions), a preliminary building program (list of desired spaces with square footages), and sometimes massing studies or test-fit diagrams to explore development options. The architect might also prepare a high-level project budget estimate or yield study, and a preliminary project schedule (though at this stage, timelines are rough). All this gives the owner a “go/no-go” basis for proceeding.

Timeline:

The Pre-Design phase can range from a few weeks to a few months, depending on the complexity of the project and how quickly information can be gathered. A straightforward interior fit-out might have a brief pre-design, whereas a large ground-up development (with site acquisitions, multiple stakeholders, etc.) could require extensive study.

Stakeholders & Coordination:

The owner (developer) and architect are the primary participants in Pre-Design. The owner provides their goals and constraints, while the architect leads research and analysis. Other professionals may be consulted as needed – for example, a surveyor to provide a land survey, a geotechnical engineer if soil tests are required, or a zoning/code consultant for tricky regulatory questions. In some cases, experienced developers handle parts of Pre-Design in-house, but they often still rely on architects for technical analyses (especially zoning in NYC). Early input from an attorney or land-use expert may occur if there are potential legal hurdles (like obtaining a variance). Overall, this phase is collaborative and often iterative: expect lots of questions and information exchange.

Approvals:

No formal government approvals are obtained during Pre-Design. This phase is about groundwork and planning. However, it should surface any special approvals the project will need later. For example, if a zoning variance, special permit, or Landmark Preservation Commission approval is required, identifying that in Pre-Design is crucial so that the project timeline can account for those procedures. Internally, the outcome of Pre-Design is typically a decision by the owner on whether to move forward with the project (and under what parameters).

Costs:

Pre-Design services are often contracted as an additional service outside the main architectural fee, or as a small initial portion of it. Some architecture firms may offer feasibility studies for a flat fee or as part of a proposal to win a project. In terms of effort, Pre-Design is relatively limited – often accounting for a very small percentage of the overall design work (sometimes on the order of 0–5% of total architectural fees). The owner might incur other direct costs at this stage, such as paying for a survey, site inspections (like environmental tests or hazardous materials checks on an existing building), or preliminary consulting reports. Being thorough in Pre-Design can save money later by catching red flags early. Once this phase is complete and the project is deemed feasible, the formal design work begins.

Schematic Design (SD)

Once the project’s parameters are defined, it moves into the Schematic Design phase. This is the first step of actual design work, where the architect translates the project requirements into an initial building design concept. In Schematic Design, the emphasis is on exploring ideas and defining the general shape and layout of the project. The architect will develop several alternative design schemes for the client to consider, using sketches, diagrams, and maybe simple 3D models or massing studies. Through an interactive process of review and feedback, these options are narrowed down to one final schematic design that meets the client’s goals.

During Schematic Design, the architect establishes the basic form and floor plan of the building. Key decisions made in this phase include the building’s overall footprint and orientation on the site, the organization of interior spaces, and the look of the building massing (its height, volume, and general exterior appearance). There is a lot of back-and-forth with the client at this stage – Schematic Design is often quite exciting and creative, as the vision starts to take shape from the blank page. While schematic drawings are not highly detailed, they illustrate the fundamental design intent. Typically, the architect prepares a site plan, rough floor plans, and exterior elevations or massing views to communicate the concept. Critical technical considerations are also researched now: for example, the architect will revisit the zoning and building code analysis in light of the proposed design to ensure it’s feasible (e.g. checking building height limits, occupancy classifications, exit requirements, etc. in NYC’s codes). If the project is pushing any limits, adjustments are made while things are still fluid. By the end of Schematic Design, the goal is to have the owner formally approve a design direction – a clear concept to develop in further detail next. Along with that, a preliminary construction cost estimate is usually prepared (either by the architect, a cost consultant, or an early input from a contractor) so the owner can verify the concept aligns with the budget before proceeding.

Schematic Design – What to Expect:

- Deliverables: At the conclusion of Schematic Design, the architect will produce a package of conceptual design drawings for the owner’s review. These typically include a site plan (showing the building’s location on the property and basic site features), floor plan(s) indicating room layouts and circulation at a notional scale, and perhaps building elevations or 3D perspective renderings to convey the architectural character. The drawings will be more diagrammatic than technical – they’ll show the general layout and massing, but not every dimension. In addition, the architect often provides an outline specification or description of key materials (for example, noting anticipated structural system, facade materials, major building systems in a summary form). Crucially, a preliminary cost estimate or order-of-magnitude construction cost is typically included as a deliverable of SD. This might be a cost per square foot analysis or a budget based on current market data. The purpose is to confirm that the design as proposed is financially viable before more detailed design work is done.

- Timeline: Schematic Design often takes on the order of 1 to 3 months for many commercial projects. The exact duration depends on the project’s complexity and the client’s decision-making speed. In an active real estate market like NYC, developers may push for an efficient SD process to get to a “go” decision quickly, but it’s important to allow enough time for exploring options. Expect a series of design meetings or presentations during this phase – the architect might present, say, 2–3 different schemes initially, then refine one based on feedback, and present an evolved schematic for approval. Rushing through SD is not advised, since changes at this stage are relatively easy to make compared to later.

- Stakeholders & Coordination: The primary players in SD are the architect (design team) and the owner/client. The architect’s team (which may include an interior designer or visualization specialist for renderings) will be generating the design ideas. The owner provides input on functional needs (for example, a developer might specify how many square feet of rentable space they need, or particular features attractive to tenants) and aesthetic preferences. At this phase, involvement of engineering consultants is usually light but not absent – often the architect will consult a structural engineer to confirm the viability of the proposed building span and structural system, or an MEP engineer in a preliminary way (e.g., to reserve space for mechanical equipment or shafts in the layouts). For a ground-up commercial building, sometimes a civil engineer is engaged early to look at site utilities or grading. However, detailed engineering comes later; in SD the focus is on architectural layout. Regular meetings (weekly or bi-weekly) between the architect and owner are common to review progress. If the developer has other stakeholders (investors, end-users, etc.), they might also review the schematic plans now to ensure everyone’s expectations are aligned.

- Approvals: There are no formal governmental approvals achieved during Schematic Design. However, in some cases, the schematic design may be used for preliminary discussions or community outreach. For instance, a developer might present a schematic design to a corporate board, to potential tenants, or informally to a NYC community board or landmarks commission staff to get early feedback. These are not official approvals, but rather checkpoints that can smooth the path later. The real approval at the end of SD is the owner’s approval of the design concept. Once the client signs off on the schematic design (and usually, on the updated budget estimate), the project can move forward to detailed design.

- Costs: In terms of architectural fees, Schematic Design typically represents around 10–20% of the total design fee (commonly ~15% as a rule of thumb). By the end of SD, the owner will have expended this portion of the design budget. It’s an important checkpoint financially: the preliminary cost estimate delivered now should be compared against the target budget. If the design is over-budget, this is the stage to address it – possibly by scaling back scope or choosing more cost-effective design options – before significant resources are invested in detailed drawings. From the owner’s perspective, changes are cheapest to make in Schematic Design; once the project moves into later phases, altering fundamental aspects of the design will cost more in redesign effort and potentially cause schedule delays. Thus, clients should expect a candid budget review at SD completion. Some projects even involve a professional cost estimator or contractor at this point to validate the architect’s assumptions. Making thoughtful decisions in Schematic Design sets the financial foundation for the project.

Design Development (DD)

After a schematic design is approved, the project enters Design Development, where that concept is refined and detailed to a much greater extent. If SD answered “what” the building will generally look like and contain, Design Development answers “how” it will all work and what it’s made of. In this phase, the architect and engineers dive deeper into the design, adding resolution to all aspects of the project. Key objectives of DD are to fix and describe the size and character of the building in terms of architecture, structure, and systems. This includes developing comprehensive floor plans, sections, and elevations with accurate dimensions, and selecting major materials and finishes.

One hallmark of Design Development is that engineering integration kicks into full gear. Whereas in Schematic Design the mechanical or structural systems might have been just conceptual allowances, now the engineering consultants fully join the effort. The structural engineer will design the structural framework in detail (e.g., specifying column placements, beam depths, slab thicknesses). Mechanical/HVAC engineers will lay out ductwork, machine rooms, and HVAC equipment. Electrical and plumbing engineers begin routing main runs and defining equipment spaces. All these systems must be coordinated with the architecture; part of DD is an iterative back-and-forth to ensure, for example, that the ceiling heights can accommodate ductwork, or that the electrical room is sized correctly. The architect’s role is to synthesize these inputs and adjust the design as needed so everything fits together.

During DD, the design is also fleshed out visually and materially. The architect will present the owner with options for materials and finishes – for a commercial project, this might involve decisions on the façade cladding (glass, metal panels, stone, etc.), the window systems, interior lobby designs, lighting fixtures, and so on. Many clients find this part enjoyable as the building’s aesthetic comes into focus, though it can be overwhelming given the number of choices. The architect will guide the owner through these decisions, balancing design quality, durability, and cost for each selection. By the end of Design Development, most major design decisions should be made and the project’s design should be essentially “locked in.” In fact, it’s common for the architect to have a formal owner sign-off at DD completion, indicating that the owner approves the developed design (which includes the specified materials and systems). This sign-off is important because changes beyond this point become increasingly difficult and expensive.

Design Development – What to Expect:

Deliverables:

Design Development produces a far more detailed set of design documents than Schematic. The architect will deliver updated plans, sections, and elevations now drawn to scale with dimensions, showing the building’s layout and form in a finalized way. Wall sections or construction details might be started to illustrate how key parts of the building will be built (for example, how a typical exterior wall assembly layers together). A door and window schedule might appear in this phase, listing proposed types and sizes. In addition, an outline specification is typically expanded – the architect will provide specifications or descriptions for all major materials, products, and systems (e.g. type of roofing, type of HVAC system, interior finishes for representative areas). Renderings or computer models might be updated to reflect the chosen design, giving the owner a realistic preview of the final product. Also, the cost estimate should be revised at the end of DD. With more detail in hand, the project’s estimated construction cost can be calculated more accurately than it was in SD. If the project is large, sometimes a professional estimator is engaged at this point to provide a detailed preliminary bid or probable cost report. The goal is to ensure the design as developed is still on budget, before committing to construction documents.

Timeline:

Design Development for a commercial building often takes on the order of 2 to 4 months, but this can vary widely. On some projects DD is a fairly swift refinement; on others, it can stretch longer if there are extensive owner reviews or if significant design changes are made due to budget or other reasons. It’s common to have at least one or two intermediate review meetings during DD (for example, at 50% DD) so the owner can see progress and provide feedback or approvals on key items. Since multiple consultants are involved, coordination can slow things down – one practical tip in NYC is that the owner should be timely in making material decisions and providing any necessary direction (like tenant requirements) because late decisions can ripple into schedule delays.

Stakeholders & Coordination:

Collaboration is intensive in Design Development. Along with the architect’s design team, all the consulting engineers (structural, mechanical, electrical, plumbing, fire protection) are actively producing drawings and calculations. They must constantly coordinate with each other – for example, structural beams can’t run where an air duct needs to go, so conflicts are identified and resolved through coordination meetings or clash-detection if using BIM (Building Information Modeling). The architect orchestrates this process, ensuring that the architectural design accommodates these systems (often involving some tweaks to plans or ceiling heights, etc.). The owner remains closely involved as well: expect regular design meetings focused on specific topics (façade design, lobby design, MEP systems overview, etc.).

The owner’s decisions on materials, finishes, and equipment are needed throughout DD. Also, if the owner has other parties to satisfy – say, a future tenant or a lender – this is the phase where those parties might review the design. For instance, a tenant who has pre-leased space might want to see and approve certain layout aspects, or a lender might require that the design (and updated cost estimate) is in line with what was agreed in financing. Good communication between owner, architect, and consultants is key in DD to prevent misalignment.

Approvals:

Typically, no new public approvals are finalized during Design Development, but it’s a preparation stage for approvals that will come next. In some projects, if a discretionary approval (like a zoning special permit or a landmarks approval) is needed, the DD-level documents may be used to make that submission. For example, in NYC, if the building is in a historic district, by the end of DD the architect might prepare presentation drawings and file an application with the Landmarks Preservation Commission to obtain a Certificate of Appropriateness. Or if a zoning variance is required, the design at DD stage is usually detailed enough to present to the Board of Standards and Appeals or City Planning. These processes would run in parallel with the CD phase. Aside from such cases, the main “approval” in DD is again the owner’s approval of the developed design (often documented in writing). This internal sign-off indicates that the project can proceed to final Construction Documents without major design changes.

Costs:

By the end of Design Development, a significant portion of the design work is complete – typically, combining SD and DD, roughly 30–35% of the architect’s fee has been expended (SD ~15% + DD ~20% of fee on average). Clients should expect that design fee billings to date will reflect this progress. Importantly, the construction cost estimate at DD should be taken seriously as a checkpoint. If this estimate shows the project is over budget, the team will likely engage in value engineering now – which means revising the design or specifications to reduce cost (for instance, choosing a less expensive facade material, or simplifying certain elements). It’s far better to address budget issues in DD than later during bidding or (worse) during construction. Changes in DD can usually be made within the existing design process, whereas after CDs are done, redoing work is inefficient and may incur extra fees. Therefore, owners should allocate time and possibly a contingency in their budget for a thorough cost review at the end of DD. Once everything looks good (design and budget aligned), the project moves on to the detailing and documentation phase.

Construction Documents (CD)

The Construction Documents phase is where the project’s design is translated into the detailed instructions for construction. By this stage, the design is settled – now the task is to produce comprehensive drawings and written specifications that contractors and city plan examiners can rely on. In essence, the project team (architect, engineers, and other consultants) creates the “blueprints” for the building in exhaustive detail.

During Construction Documents, every aspect of the building is delineated, from overall plans down to specific details like wall sections, door schedules, and finish details. The architect coordinates closely with the structural and MEP engineers (and any specialty consultants, such as elevator, facade, or IT/security consultants) to ensure the drawings are fully integrated. This phase demands a rigorous quality control process, as inconsistencies or omissions in the documents could lead to confusion or change orders during construction. A well-executed CD set will minimize surprises in the field and allow contractors to price the work accurately during bidding.

In NYC, the Construction Documents phase also involves the critical step of obtaining a building permit. The architect will prepare a set of drawings specifically for permitting, often called the permit set, which is submitted to the NYC Department of Buildings (DOB) for plan review. This set must demonstrate code compliance (zoning, building code, energy code, accessibility, etc.). It usually includes the architectural and engineering plans necessary for DOB’s examination, but might not have every tiny detail that the full construction set will contain. In fact, many architecture firms produce two parallel sets of drawings: one for permit application and one “Issued for Construction” (IFC) that is completed thereafter.

The permit process can take some time in NYC, so submitting the permit set as soon as key information is available is wise – while the review is ongoing, the team can continue adding final details to the construction set. Once DOB reviews the plans, they may require corrections or clarifications; the architect responds to these to obtain approval. (It’s common in NYC to use a filing representative or expeditor to help navigate DOB procedures and paperwork.) By the end of the CD phase, the aim is to have a full approved set of plans and a ready-to-build package, so the project can proceed to contractor bidding and then construction.

Construction Documents – What to Expect:

Deliverables:

The outcome of this phase is a complete, coordinated set of construction drawings and specifications. This will be a hefty package that includes: Architectural drawings (cover sheet, code analysis sheet, dimensional floor plans of every level, roof plan, elevations, building sections, wall sections, enlarged plans of key areas, detail drawings for connections/joints, door and finish schedules, etc.); Structural drawings (foundation plans, framing plans for each level, structural details for beams/columns/connections, schedules for structural elements); Mechanical/HVAC drawings (equipment layouts, ductwork and piping plans, schedules for air handling units, etc.); Electrical drawings (lighting plans, power plans, panel schedules, one-line diagrams); Plumbing drawings (plumbing and drainage plans, riser diagrams, fixture schedules); and any other systems like fire protection, fire alarm, or specialty systems drawn out.

In addition to drawings, the architect produces a Project Manual or specification book that provides written specifications for materials, products, installation techniques, and quality standards (for example, spec sections will cover everything from concrete and steel to finish paints and door hardware). All these documents together form the technical instructions for the contractor. Another crucial deliverable is the permit application package submitted to DOB: typically a subset of the drawings focusing on code and zoning compliance, along with all required forms and filings (energy compliance statements, schedules of occupancy, etc.). Finally, if not already obtained earlier, any third-party approvals (like final Landmarks approval, if applicable, or elevator permits from DOB, etc.) must be secured during this phase. By the end of Construction Documents, the owner will have in hand the full set of plans that contractors will bid on and build from.

Timeline:

The Construction Documents phase is often the longest single phase of design. For a mid-size commercial building, it might take 3 to 6 months to produce complete CDs, but it could be shorter for simpler projects or significantly longer for very large/complex ones. The schedule depends on how many consultants are involved and how coordinated the process is. Overlap can occur – for example, some early bid packages (like excavation/foundation drawings) might be issued before the entire set is finished, in a fast-track scenario. In NYC, one must also factor in the DOB review time: it can take several weeks to a few months from initial submission to get a permit, depending on backlogs and how quickly any objections are resolved. Owners should plan the project timeline with some buffer for the permit process. Frequent coordination meetings happen in this phase among the design team, and periodic milestone reviews with the owner (e.g., 50% CD review, 90% CD review) are wise to ensure the documents align with the owner’s expectations. It’s a highly technical phase with less “glamour” than earlier design stages, but absolutely vital to the project’s success.

Stakeholders & Coordination:

During CDs, the architect takes on the role of a project coordinator and technical lead, driving the myriad pieces into a unified whole. The full consultant team is active – all engineers and any specialty designers (lighting designer, facade consultant, interior designer for lobbies or tenant areas, etc.) produce final drawings/specs for their disciplines. There is constant coordination: the architect checks that engineering elements fit within architectural spaces, and that specs don’t conflict. The owner’s role during CDs is usually to review progress and provide timely decisions on any remaining choices (perhaps minor finish details or alternates). The owner might also start to engage a construction manager or advisor at this stage to provide input on construction logistics or packaging of the work. If not already done, the selection of an expediter to handle permit filing is typical in NYC – this person/team works with the architect to prepare the DOB submission, making sure forms are correct, required signatures (like owner’s statements, special inspection agreements) are in place, and addressing any city comments.

There may also be coordination with other agencies: for example, projects in NYC often require a separate filing for sprinkler and fire alarm systems, or coordination with the Department of Transportation if sidewalks/street work is involved, etc. The architect guides these processes, often alongside legal counsel or expediters for specific filings. The key to CD phase is meticulous communication: expect a lot of detailed questions and clarifications within the design team. From the client’s perspective, this phase might seem less interactive than previous ones, but it’s important to remain available to the architects/engineers for any clarifications (like confirming a finish material or an equipment choice) promptly, to avoid slowing down the progress.

Approvals:

The building permit is the primary approval sought during Construction Documents. In NYC, once the DOB approves the submitted plans and issues a construction permit, it’s a major milestone – it legally allows construction to commence (assuming a licensed contractor is in place). To get there, the plans must comply with all applicable codes and zoning. The architect responds to any DOB objections or comments as part of this approval process.

It’s worth noting that NYC has various interim sign-offs that might be part of CD phase: for instance, if the project needed an Environmental Control Board approval or a BSA (Board of Standards and Appeals) variance, those would need to be secured by now and reflected on the plans. The owner should ensure that any financing or insurance requirements tied to the permit are ready as well (lenders often won’t release funds until permits are obtained). By the end of CDs, the project should have all necessary approvals to start construction: permit in hand and any other relevant agency consents. If the project is bidding out to contractors, the permit can sometimes still be in final processing while bids are solicited, but practically it’s ideal to have the permit or be very close to it when selecting a contractor.

Costs:

Construction Documents typically consume the largest chunk of the architect’s fee – often around 35–50% of the total fee (commonly cited around 40%), reflecting the substantial work required to produce detailed plans. Clients will see the billing corresponding to this intensity. Beyond design fees, there are a few other cost considerations in this phase: filing fees to NYC DOB (which are based on the building’s square footage and/or estimated cost – NYC charges a fee for plan examination and another for permit issuance); fees for any third-party consultants needed for filings (e.g., expeditor fees); and possibly costs for pre-construction services if a contractor or construction manager is doing a constructability review or cost estimate as the CDs are completed.

On the construction cost side, by the time CDs are done, the owner should have a very clear idea of the expected cost of the project. If competitive bidding is planned, the finished CDs will be used by contractors to provide final bids – ideally these come in at or near the earlier estimates if there were no big changes. It’s prudent for an owner to maintain a contingency fund even at this stage (perhaps 5-10% of project cost) to account for any last-minute scope adjustments or unforeseen conditions that could arise later. But a thorough CD phase, with robust quality checks, is the best defense against unexpected costs during construction.

Bidding & Negotiation

With a complete set of construction documents ready, the focus shifts to procuring a contractor to build the project. In the Bidding & Negotiation phase, the project is presented to the marketplace of builders for pricing. For commercial developments in NYC, this phase is crucial to ensure you get a qualified contractor at a fair price – construction costs in the city are significant, so a well-managed bidding process can save money and time.

There are a couple of ways this phase might unfold: competitive bidding or negotiated contract. In a competitive bid scenario, the architect (on behalf of the owner) solicits bids from multiple general contractors. The architect will issue the bid package – usually the construction drawings, specifications, and any special instructions – to a list of pre-qualified contractors. Often, there’s a formal bid period (say 2-4 weeks) during which contractors study the documents, visit the site, and prepare their price proposals. The architect assists the owner by answering any RFIs (Requests for Information) that bidders have; if clarifications or changes to the documents are needed, the architect will issue addenda to all bidders so everyone bases their pricing on the same information. Sometimes a pre-bid meeting is held, where all interested contractors are invited to meet at the site and ask questions – this is common for public projects, but even private developers in NYC often do site walkthroughs with bidders for complex jobs.

When bids are received, the owner and architect review them together. This involves comparing the contractors’ proposed prices, but also their qualifications, assumptions, and construction schedules. The architect will help create a bid tabulation to evaluate each bid apples-to-apples. If one bid is significantly lower or higher, the architect might help investigate why (e.g., did that contractor misunderstand something or include a different scope?). At this point, the owner may choose to negotiate with one or more of the top bidders. For instance, if the lowest bid is above budget, the owner with the architect’s help can identify areas to cut costs (this may lead to a value engineering exercise where certain materials or features are adjusted).

The architect then might issue a revised drawing or addendum reflecting those changes and ask bidders to adjust their pricing accordingly. Finally, the owner will select a contractor (not always the cheapest, but the one that offers the best value and capability). The “Negotiation” part of this phase refers to finalizing the contract terms with that chosen contractor – things like confirming the construction schedule, any clarifications in scope, and formally agreeing on the contract sum or guaranteed maximum price. Once both parties are satisfied, a construction contract (typically AIA’s standard owner-contractor agreement or similar) is signed, and the contractor is given the green light to proceed.

Bidding & Negotiation – What to Expect:

Deliverables:

The primary deliverable of this phase is the selection of a contractor and an executed construction contract. Leading up to that, several interim deliverables are involved: the architect will prepare Bid Documents (which may simply be the construction drawings and specs plus a cover letter or an Instruction to Bidders document outlining how to submit bids). The owner or architect might also include a bid form that contractors fill out, ensuring they all provide the information in a structured way (e.g., listing key subcontractors, confirming they have included all alternates, etc.). During bidding, any Addenda (written or drawn clarifications) issued become part of the bid documents. After bids are received, the architect typically provides a bid analysis report or recommendation letter to the owner, outlining the differences between bids and any considerations.

Finally, once a contractor is chosen, the Contract Award happens – the deliverable is the signed construction contract along with a detailed schedule of values or breakdown of costs, and possibly early submittals like a preliminary construction schedule or insurance certificates from the contractor. In summary, by the end of this phase, the project team will have in hand: the contractor’s final offer (bid) accepted, a formal agreement in place, and the project ready to mobilize for construction.

Timeline:

The bidding process for a commercial project in NYC generally spans a few weeks to a couple of months. A typical timeline might be: one week to invite bidders and distribute documents, 3–4 weeks for contractors to work on their bids (including site visits and RFI exchanges), then a week or two for the owner/architect to analyze bids and conduct any interviews or negotiations. If a second round of bidding or value engineering is needed, that can add a few more weeks.

Also, if the first round of bids is unsatisfactory (all over budget, for instance), the owner might decide to rebid with a revised scope or solicit a different pool of contractors, which extends the timeline. It’s wise to allocate some float time here, because negotiating the contract (legal review of terms, etc.) can also take longer than expected. On the flip side, if the owner had a preferred contractor involved early (sometimes developers do a negotiated contract with a known contractor), then this phase might be shorter and more about finalizing terms rather than running a full bid competition. One must also consider any external schedule drivers: for example, if a financing or loan closing is tied to having a contractor on board, ensure the bidding timeline aligns with those milestones.

Stakeholders & Coordination:

The main stakeholders in this phase are the owner (and their project managers or cost consultants, if any), the bidding contractors, and the architect. The architect’s role is more advisory here – preparing the bid package, responding to contractor inquiries, and helping the owner evaluate bids. The contractors (and their subcontractors, behind the scenes) will be busy estimating costs and clarifying the scope. If the project is large, some owners hire a Construction Manager (CM) who can manage the bid process in collaboration with the architect. For example, a CM can solicit and vet subcontractor bids and provide a guaranteed maximum price to the owner. In such cases, the architect coordinates with the CM instead of directly with multiple GCs. Communication is very important in this stage: expect perhaps a pre-bid meeting (coordinated by the architect), regular RFI logs (the architect will answer questions in writing so all bidders are treated equally), and possibly scope review meetings with one or two top bidders to ensure everything is understood.

The owner will be making the ultimate decision on contractor selection, but they will rely on the architect for technical insight (did the bidder include everything per the drawings?) and perhaps rely on other consultants for financial insight (is the pricing realistic?). Once a contractor is chosen, the owner’s legal team might get involved to review the contract language, while the architect can assist by attaching the project manual and drawings as contract documents and confirming the construction obligations from the design side. In NYC, it’s also prudent to coordinate with the contractor on permitting at this point – ensure that the contractor has pulled or is ready to pull any necessary work permits (the general contractor must register with DOB and pull a permit based on the approved plans), and that insurance and site safety plans are in order. The architect might attend a handoff meeting to brief the contractor on any design intent nuances as the project transitions into construction.

Approvals:

There are typically no new governmental approvals needed during bidding itself – the focus is on contractual arrangements. Ideally, by bidding time the project’s plans have already been approved by DOB and permits are ready to be issued once a contractor is on board. (In fact, many owners time the bidding so that permit approval coincides roughly with selecting the contractor, enabling construction to start promptly after contract signing.) One “approval” that could be relevant now is from any financial stakeholders: for instance, a lender or investment committee might need to approve the selected contractor or verify that the construction cost aligns with the pro format.

This isn’t a public approval, but a private one. Another possible consideration: if the project had to go through a public bid or certain compliance (say the project has city funding or incentives requiring contractor procurement processes), those conditions must be satisfied in how bidding is handled. In summary, by the end of this phase, the project should be ready to commence construction with all city permits in place and a contractor obligated to build the project for the agreed price and schedule.

Costs:

From the design side, the Bidding/Negotiation phase usually accounts for a small percentage of the architectural fee (on the order of 5% or less). The architect’s work here is limited to issuing documents, answering questions, and assisting in evaluation. The bigger cost implications in this phase are related to the construction cost. This is when the rubber meets the road financially: the bids determine what the project will actually cost to build. An owner should have a contingency plan if bids come in higher than expected – this could mean having extra budget available or being ready to adjust the project scope. It’s common in NYC for bids to exceed initial budgets due to the city’s high labor and material costs, so savvy developers often include a buffer in their pro forma or get a cost check from a contractor earlier (during DD) to avoid surprises. The negotiation part may help reduce the cost somewhat (through scope alignment or value engineering), but owners should be realistic about market conditions.

Once a contract is signed, the contract sum is locked in (barring change orders), and the owner will be committing to monthly progress payments to the contractor as construction proceeds. In terms of immediate costs at this stage: the owner might incur some minor expenses for printing bid sets (though digital distribution is more the norm now) or for pre-construction services if they engage a contractor early. Also, typically the winning contractor will submit a construction schedule and payment schedule – aligning these with the owner’s financing draws is important for cash flow. In summary, the Bidding phase is less about design spend and more about confirming the capital expenditure for construction and making sure it fits the plan.

Construction Administration (CA)

The final phase is Construction Administration, which spans from the start of actual building work through project completion and close-out. In this phase, the project shifts into the hands of the contractor for execution, but the architect and engineers remain involved to observe the work, address issues, and support the owner in making sure the construction conforms to the design intent and quality standards. For a commercial client, this phase is where your vision becomes reality – steel is erected, concrete is poured, and spaces take shape – so it’s exciting, but it also requires diligence to manage time, cost, and quality.

It’s important to note that under a standard AIA contract, the architect is not the construction supervisor and does not direct the contractor’s means and methods. The contractor is solely responsible for site safety and construction techniques. Instead, the architect’s role during Construction Administration (often termed contract administration) is to act as the owner’s representative on design matters: reviewing the work for conformance with the drawings, and processing the paperwork that accompanies construction.

At the start of construction, typically a kick-off meeting is held with the contractor, owner, and architect to establish communication protocols, submittal schedules, and site visit schedules. Throughout construction, the architect will make periodic site visits – for example, weekly or biweekly – to observe progress and to check that the work generally adheres to the plans. After each visit, the architect issues a field report noting any observed deficiencies or deviations from the drawings.

If an issue is found, the architect communicates it to the contractor and owner, and assists in finding a solution (for instance, suggesting a fix or confirming an acceptable alternative). The architect also handles submittals: the contractor will submit shop drawings, product data, and material samples for the architect’s review. These submittals are the contractor’s detailed interpretation of the design (e.g., drawings from a steel fabricator showing exactly how the steel will be cut and connected). The architect reviews them to ensure they meet the design requirements and either approves or provides comments. This submittal review is crucial in a commercial project because it’s the last chance to catch inconsistencies or errors before fabrication and installation.

Another key part of CA is managing changes. Despite the best efforts in earlier phases, changes during construction can occur – perhaps due to unforeseen site conditions (e.g., unexpectedly poor soil requiring a foundation redesign) or owner-driven changes (like a new tenant improvement or revised finish). When a change is needed, the architect may issue a CCD (Construction Change Directive) or ASI (Architect’s Supplemental Instruction) or formally draft a Change Order in conjunction with the contractor. A change order will adjust the contract sum or time if needed, and it must be agreed upon by owner and contractor. The architect’s job is to document the change (often with revised drawings or details) and ensure the owner understands the cost/time implications as provided by the contractor.

For projects in NYC, an additional layer of oversight comes from the city’s inspection requirements. The NYC Building Code mandates that certain inspections be carried out by the design professionals or special inspectors as construction progresses. These include things like concrete strength testing, structural stability checks, plumbing inspections, energy code compliance inspections, etc. The architect will perform or coordinate Progress Inspections (for instance, checking that insulation and lighting meet energy code on site at the appropriate time). There are also Special Inspections that may be done by a third-party agency (for example, welding inspections or soil compaction tests) – the architect helps ensure these are scheduled and that reports are filed. All these inspections result in documentation (Technical Reports such as TR1, TR8 forms in NYC) that must be submitted to DOB before the project can be signed-off. The architect plays a critical role in assembling and submitting these close-out documents alongside the contractor.

As construction nears completion, the architect will do punch list inspections – walking through the building to list items that are incomplete or require correction. The contractor then addresses these items to the architect’s satisfaction. Finally, the architect assists the owner in obtaining the Certificate of Occupancy or final sign-off from DOB, which legally allows the space to be occupied. This might involve providing the DOB with final papers, such as the architect’s certification of completion, and ensuring all inspections (including elevator, fire alarm, sprinkler tests, etc.) have passed. Once everything is in order, the project is essentially finished from a design and regulatory standpoint. Construction Administration concludes with the architect issuing a final Certificate for Payment (if under an AIA contract) indicating the contractor has fulfilled their obligations, and the owner making final payments including release of any retainage to the contractor.

Construction Administration – What to Expect:

Deliverables:

Unlike other phases, Construction Administration doesn’t produce a single package of drawings at the end, but it generates many ongoing deliverables and documentation. Key items include: Field Observation Reports (the architect’s written reports after site visits, noting progress and any issues); Submittal Responses (stamped “approved” or “revise and resubmit” notations and comments on shop drawings, etc. – these become part of the project record); RFI Responses (written answers to any Requests for Information that the contractor submits when something in the drawings needs clarification); Change Documentation (sketches or drawings issued to describe any changes, along with formal Change Orders that adjust cost/time as agreed); Meeting Minutes (often, if regular construction meetings occur, either the architect, contractor, or owner’s rep will record minutes to track decisions and issues); Pay Applications (the architect typically reviews the contractor’s monthly payment requests and certifies the amount to be paid based on work completed – these certifications are a deliverable that the owner’s finance team relies on); and Close-Out Documents.

Close-out docs include the final punch list and its sign-off, warranty information and manuals for the owner (often compiled by the contractor, but the architect may review that they are complete), as well as the all-important regulatory close-out documents. In NYC, this means completed Technical Reports for all required inspections, a final sign-off from the architect and engineers that the work met the plans (often via a form or letter to DOB), and assisting the owner in obtaining the Certificate of Occupancy or a Letter of Completion. Essentially, the deliverable at the very end is an officially approved, occupiable building. The architect may also provide the owner with a set of “as-built” or record drawings if that was part of the agreement (these would reflect any changes made during construction, based on markups the contractor kept).

Timeline:

Construction Administration lasts as long as the construction itself. This could be as short as a few months for a minor renovation, or a year or more for a large building. Many commercial projects in NYC might have a 12–24 month construction period depending on size and complexity (for example, a mid-rise building might be 18 months from ground breaking to completion). During that time, the architect’s involvement is periodic but ongoing. Typically, the architect will visit the site at defined intervals – perhaps once every week or two weeks – and additionally at critical junctures (e.g., when a key milestone like structural frame completion happens, or when a specific issue requires inspection). The frequency can be agreed upon in the contract; more complex projects or more quality-conscious owners might stipulate more frequent oversight.

Importantly, the end of construction can sometimes stretch with final inspections and punch list items. Even after the main construction work is done, plan for a close-out period (maybe 1-2 months) to finish paperwork and minor corrections. So, the CA phase is the longest calendar duration of any phase, but much of the heavy lifting (design work) is already done – now it’s about monitoring and wrapping up. Owners should also be aware that unexpected delays (due to weather, supply chain issues, etc.) can prolong construction; the architect remains on call throughout, possibly under additional services if the construction extends significantly beyond the original schedule.

Stakeholders & Coordination:

During CA, the general contractor (GC) or construction manager takes center stage, as they execute the build. The owner may have a representative or project manager staying on top of the contractor’s progress, especially in commercial development where keeping on schedule and budget is critical. The architect and their engineering consultants are in a support role – they coordinate with the contractor whenever the contractor needs information or approvals. Coordination in this phase often takes the form of weekly construction meetings involving the contractor’s site superintendent and project manager, the architect (and/or an on-site architect’s rep for very large projects), the owner’s rep, and major subcontractors as needed.

In these meetings, they discuss progress, look ahead to upcoming work, and resolve any issues or changes. Also, coordination with city inspectors occurs: for example, the contractor will schedule required DOB inspections (such as plumbing inspections, electrical inspections by DOB or third parties, etc.), and the architect ensures they or the relevant engineer are present for those inspections if needed or that they get the results. For special inspections, the owner might have hired a separate Special Inspection Agency, but the architect liaises with them to get their reports and include them in the close-out package. Communication channels must remain open – expect a lot of email correspondence on submittals and RFIs. The architect might also coordinate with other designers for final sign-offs (maybe an interior designer needs to inspect a delivered finish, or an acoustical consultant needs to test noise levels). Essentially, CA is a team effort to solve problems collaboratively on the fly while keeping the project’s design intent intact.

Approvals:

A number of municipal approvals and sign-offs are finalized during Construction Administration. Key ones in NYC include: Building Department progress inspections and final inspection – DOB inspectors will come at various stages (e.g., to inspect the foundation before it’s poured, or a plumbing rough-in) and ultimately do a final inspection walk-through. The project cannot get a Certificate of Occupancy (CO) without passing these. The architect doesn’t directly control these inspections but often attends and ensures any issues noted are addressed. Special Inspections as mentioned, must all be signed off by the respective professionals and submitted. Additionally, other agencies might be involved: for instance, the Fire Department (FDNY) may need to test the fire alarm or sprinkler system before sign-off, or the Elevator Division must inspect new elevators, etc.

The culmination of all this is the issuance of a Certificate of Occupancy (for new buildings or major renovations) or a Letter of Completion (for minor projects) by DOB. Leading up to that, the architect usually submits a final TR8 (Energy Code sign-off) and EN2 (energy commissioning, if applicable), and the engineers submit any final letters (like sprinkler sign-off letters). The owner will also need to ensure all final paperwork is in, such as contractor’s completion sign-off, asbestos abatement certificates (if relevant), etc. It’s a lot of paperwork, but in NYC it’s well-defined. The architect often helps the owner compile these documents or provides a checklist of what’s needed. Only once all approvals and inspections are successfully closed can the building legally open for use. Getting to this finish line requires diligence; a good architect will help shepherd the project through it, working closely with the contractor and expeditor to tie up all loose ends.

Costs:

During Construction Administration, the primary costs are those associated with the construction itself – i.e. the contractor’s monthly requisitions for payment as work progresses. The owner will be paying the contractor per the agreed schedule of values, usually monthly. The architect’s role here is to verify the amounts (often via a percent-complete estimate) and certify payment. Architecturally, CA is typically about 15–20% of the design fee. This fee covers the architect’s time for site visits, meetings, submittal reviews, and so on. One thing owners should note is that if the construction phase extends much longer than expected or becomes more complicated (say, because of many unforeseen issues), the architect may be entitled to additional services fees for the extra time spent. So it’s important to have a clear understanding with the architect of what the CA fee assumes (e.g., a certain number of site visits or a certain duration). Aside from fees, contingency funds come into play during CA. A savvy commercial client will keep a contingency (often 5-10% of the construction cost) to cover any change orders or unexpected costs.

Very few large projects go to completion with zero changes – there could be owner upgrades, minor design tweaks, or true surprises (like discovering underground conditions) that cost extra. These changes usually mean extra payments to the contractor, and potentially small added design fees if they require significant redesign. Having this reserve in the budget avoids panic when something inevitably comes up. Lastly, as the project nears completion, there are costs for final inspections and permit close-outs (DOB charges for the Certificate of Occupancy, for example, and there may be costs for final utility hookups, etc.). The owner should ensure all those end-game costs are covered. In summary, good financial management during CA means monitoring the contractor’s billed work against actual progress (the architect helps with that by certification), keeping change order costs within the set contingency, and avoiding scope creep. When CA concludes, all that should remain is for the owner to finalize any operational expenses and then enjoy the finished building.

Conclusion

Navigating the architectural design process in New York City’s commercial real estate scene can seem daunting, but breaking it into these standard phases makes it far more manageable. From Pre-Design due diligence to Schematic Design’s big ideas, through the detail refinement of Design Development and the technical rigor of Construction Documents, and finally into Bidding and Construction Administration, each phase has a distinct purpose. By clearly understanding what each stage entails, commercial clients can better plan their projects, anticipate requirements, and actively participate in the process at the right times. Importantly, following the AIA-recommended phases ensures that no critical step is skipped – this structured approach helps align expectations between the owner, architect, and contractors. It also facilitates smoother coordination with city agencies, which is crucial in a place like NYC with its formidable regulations.

For New York City developers and property owners, appreciating these phases means being prepared for the journey of a project. You’ll know, for example, that significant design decisions (and cost confirmations) happen early in Schematic and Design Development, that detailed coordination and permit approvals occur during Construction Documents, and that having the architect’s oversight during construction is vital to handle issues and secure final approvals. Each phase builds on the previous, and when executed well, leads to a successful project delivered on time and on budget.

Our firm has guided many clients through this entire process – from the first sketch on paper to the day the doors open. We understand the unique challenges and opportunities of commercial development in NYC, and we tailor our services to meet those needs at every phase. Ready to turn your development vision into reality? Contact our firm today to discuss your project. We’ll expertly lead you through all the architectural design phases, ensuring a smooth and efficient journey to a completed building that achieves your goals.